The rangatira wāhine who were prevented from signing te Tiriti o Waitangi

Ko ngā rangatira wāhine i aukatihia ai ā rātou haina i te Tiriti o Waitangi

Witnesses told the Tribunal that the patriarchal attitudes of British officials prevented some rangatira wāhine from signing te Tiriti. Two such women cited in evidence were the daughter of Te Pehi (although no witness gave her name), whose husband also refused to sign when his wife was barred (Rīpeka Evans, doc A21(external link); Lee Harris, doc A23)(external link), and Hine Aka Tioke, of Kahungunu (Tina Ngata, doc A88(external link)).

The daughter of Te Pehi

- “A specific example of this is that in 1840 the daughter of the Ngāti Toa chief, Te Pehi, was not permitted to sign Te Tiriti because she was a woman. This restriction was imposed by colonial officials who did not recognise that women of rank represented the mana of their people. This was an early indication that relations between Māori women and the colonial state would be problematic.” (Rīpeka Evans, doc A21, p 11)(external link)

- One story recorded about the daughter of Ngati Toa Rangatira, Te Pehi is that she was not permitted to sign and her husband took offense and refused to sign also as this was taken as an insult to both the mana of his wife and himself. (Lee Harris, doc A23, p 5)(external link)

Hine Aka Tioke

- “The level of economic and political power in the hands of wahine Māori was unconscionable to colonial perspectives of the time. Even though women were significant landholders and political leaders right up to the signing of the treaty, the inability of colonial mindsets to accept such equitable power distribution was reflected in the fact that wahine leaders and landholders were in many cases disallowed or discouraged from signing Te Tiriti o Waitangi by the men who were charged with collecting signatures. One such example of this is the story of Hine Aka Tioke, of Kahungunu, who was refused the right to sign Te Tiriti because the officials at the time believed that women had no constitutional power to sign contracts.” (Tina Ngata, doc A88, p 12)(external link)

Tina Ngata at Te Mānuka Tūtahi Marae, Whakatāne

Other wāhine prevented from signing te Tiriti o Waitangi

- One of our relatives was going to sign Te Tiriti o Waitangi, but she was not allowed to sign because the Crown did not allow women to have voting and signing rights, as these were not recognised. This was written in a waiata passed down the generations. I am endeavouring to find out more information about this from my whānau. (Elle Archer, A154(a), p 3)(external link)

- Two rankatira wāhine at Akaroa signed Te Tiriti in May 1840, and one did not. She came over to sign it and she looked at the Crown representatives, heard what they said, and she said, ‘Kuware.’ They’re rubbish. They know nothing. And walked away. (Ema Weepu, doc A136)(external link)

Note, NZ History records only two rangatira signed te Tiriti at Akaroa and identifies neither as women. Akaroa, 30 May 1840 | NZHistory, New Zealand history online(external link).

Ema Weepu (right) with whānau at Ngā Hau E Whā, Christchurch

What witnesses said

- “Women were political leaders, and made valued contributions to their communities, but this was not always recognised or acknowledged by Pākehā at the time. This attitude shaped how Pākehā collected information in the colonial period and in turn influenced the writing of New Zealand history which has not adequately encompassed nor fully recognised Māori women’s political and economic leadership in the pre-1840 world. This is colonialism in action and is derived from imposing a western and patriarchal understanding of gender and gender roles upon te ao Māori. Western interpretations of politics and leadership as a male activity meant that Māori women were not sought out for information, nor recognised as having authority and mana in the political realm. This partly helps to explain why there are only 13 female signatories to Te Tiriti o Waitangi.” (Professor Angela Wanhalla, doc A82, p 3)(external link)

- “At least thirteen Māori women signed the Treaty of Waitangi, several more are known to have been asked to sign the Treaty by respective hapū and iwi, however they were denied this right by colonial office men taking the Treaty around. Incidences of Māori women of rank not being accorded the right to vote were, according to [Tania] Rei, imposed by colonial officials who did not recognise that women of rank represented the mana of their people. The colonialist perception of Māori women was the same as their view of Pākehā women, subservient and domestic. These perceptions took hold in the relationships between colonialists and Māori, redefining the role of Māori women and changing the paradigm in terms of Māori thinking.” (Materoa Dodd, doc A98, p 13)(external link)

- “In pre-1840 times in Waikato, tāne and wāhine were equal. I was told that they did not let the women sign, out of protection. This was so that if anything was to happen in the future, it would not be our woman that took the blame. It would be our men. It was about kaitiakitanga and making sure the women are protected. However, on reflection, the influence of Christianity prevented wāhine from signing, even though they held chiefly positions. Christianity made it difficult for settlers to perceive wāhine holding autonomous leadership roles. Some iwi were against wāhine signing because the negotiation process was the Tāne’s role.” (Paihere Clarke, doc A141, p 5)(external link)

- “One of the main tikanga that was undermined through Christianity and was obvious at the signing of te Tiriti o Waitangi was the right of women to speak and decide. For example, the signing of te Tiriti, the treaty discussions were held with Māori men and Māori men began to think they had status. In the very short space of time it went from tū kotahi with men and women in te ao Māori, to role division and speaking rights carrying mana went with men.” (Moe Milne, doc A62, p 27)(external link)

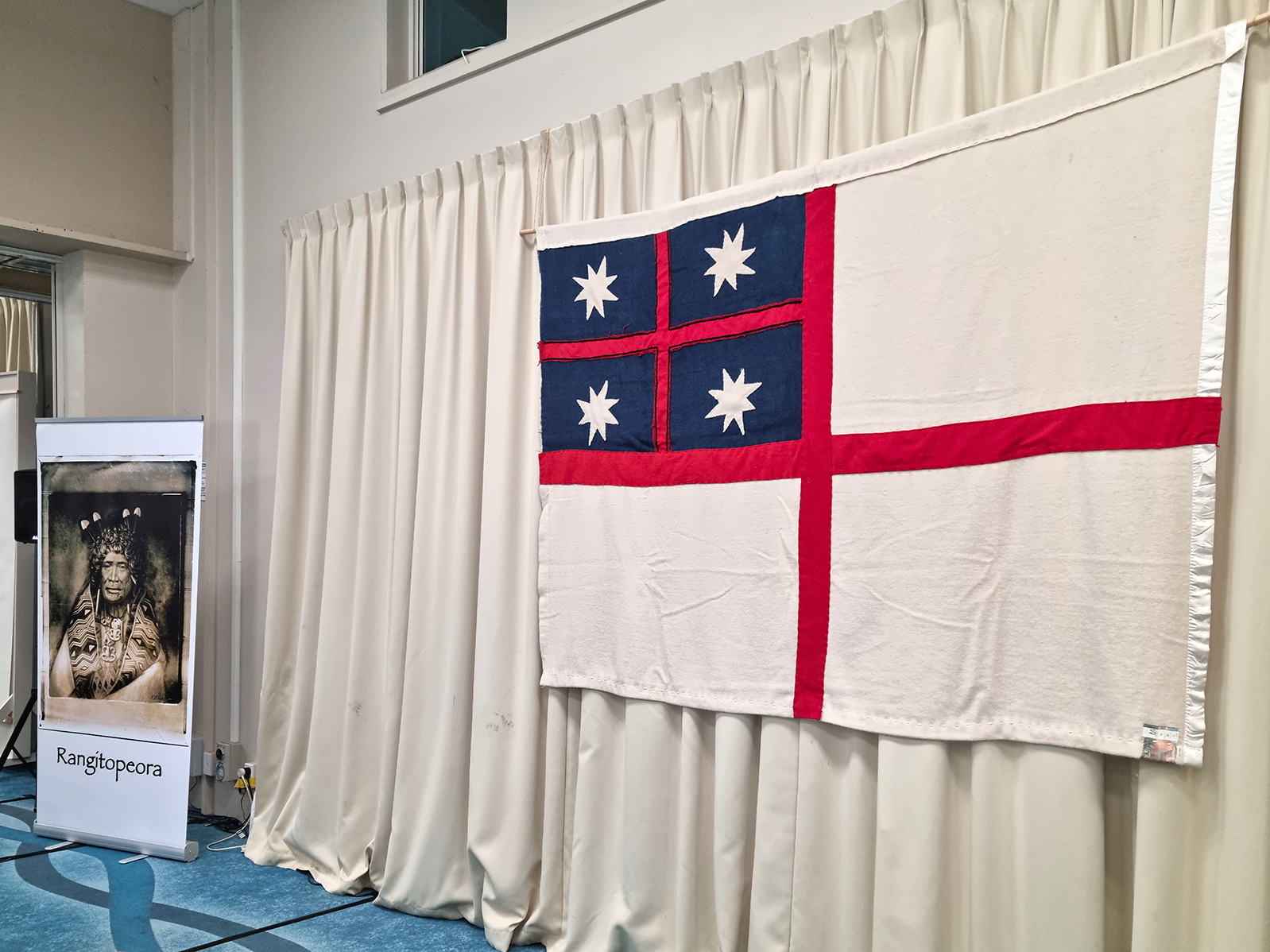

- “E whakamārama ana i te mana o te wahine i tana mana rangatira. He rite tonu tēnei mana ki te mana o ngā wāhine tokorima nā rātau i haina te tiriti o Waitangi. I kitea e o rātou iwi ko rātou ngā mea tōtika ki te haina i te Tiriti ... te mana i haere taketake mai ki te wahine mai i a Papatuānuku, me te mana i tukuna ki ngā wāhine tokorima rā, i haere mai o rātou ake iwi. ... Ko wēra i haina i kitea e ngā hoia he rangatira, ko Rangi Topeora i Kapiti, ko Kāhe TeRau-o-te-Rangi i Te Whanganui-a-Tara, Ko Rere-o-Maki i Whanganui, ko Ana Hamu i Waitangi, ko Erenora i Kaitaia.” (Dr Hiria Hape, doc A114, p 32)(external link)

- “Ki ahau nei kāre tonu i te mōhio whānuitia i te motu, tokorima ngā wāhine rangatira i haina te Tiriti o Waitangi, he tū rangatira ki roto i o rātou iwi. He nui atu ngā wāhine i pirangi ki te haina i te Tiriti, engari i aukatia mai e ngā hōia.” (Dr Hiria Hape, doc A114, p 33)(external link)

- “Te Tiriti was initially only signed by men. It is estimated that around 40 chiefs signed te Tiriti on the 6th of February 1840. By the end of the year, around 500 other Māori, including 13 wāhine, had put their names or moko to the document. The fact that so few women signed, was not because their own people prevented wāhine Māori from signing. Rather, it reflects the fact that the colonisers only acknowledged male power. In the East Coast and elsewhere women signed as equals with their menfolk.” (Cletus Maanu Paul, doc A51, p 4)(external link)

- “The status and roles of wahine Maori were, in many ways, an anathema to colonial Britain and Europe at the time of contact. Where sexual expression was condoned or celebrated for Maori, it was condemned by colonisers. While Māori female elders were repositories of sacred knowledge, women were restricted from even attending school in Britain and Europe. Even though women were significant landholders and political leaders at the time of the Treaty, they were in many cases disallowed or discouraged from signing by the men who were charged with collecting signatures around the country.” (Mereana Pitman, doc A18(a), p 4)(external link)