Have these stories about atua whāea been reconstructed over time? If so, how?

I roto i ngā tau, āe rānei kua whakatauritetia ēnei pūrākau mō ngā atua whāea me ngā tipuna whāea? Pēhea nei?

A large number of witnesses focused on the impacts of colonisation on the stories of atua whāea – both in their transmission from generation to generation, and in the changing status held by atua whāea within Māori spiritual narratives. Witnesses explained how atua wāhine were misconfigured in the accounts of ethnographers and settlers who came from a patriarchal European culture, viewed Māori spirituality through a Christian lens, and only saw tāne as sources of mana and mātauranga. Witnesses argued that these accounts influenced how atua whāea were viewed and thought of by Māori. However, in spite of these forces, witnesses emphasised that atua wāhine have retained their significance. As one witness, Jane Ruka, said: “Despite the rise of patriarchy, brought in by colonisation, we managed to retain Atua Wāhine.” (doc A135, p 2(external link))

Witnesses presented various perspectives on Io-matua-kore (Io the parentless), who some consider the highest atua. While some witnesses attested these narratives have always been part of te ao Māori, some claimed they reflected the influence of Christianity with its singular, supreme God.

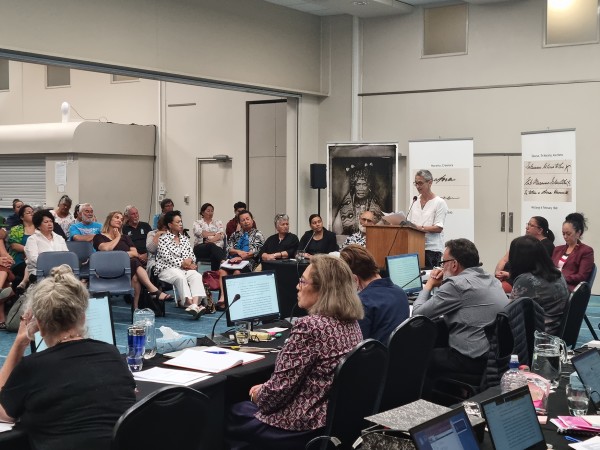

Dr Ani Mikaere addressing panel and audience at Turner Centre, Kerikeri