Whakawhānau: birthing, menstruation, and other aspects of whānau and wāhine health

Ko te whakawhānau: te whakawhānau, te waikura, me ētahi atu āhuatanga e pā ana ki te whānau me te hauora o ngā wāhine

The whānau was a crucial social unit within pre-colonial Māori society – consisting of multiple generations and existing within the context of the hapū. The continuation of the whānau was tied to te whare tangata and thus, tikanga around key aspects of wāhine health – pregnancy and birth, menstruation, and puberty were crucial in pre-colonial Māori society. Witnesses said these tikanga reinforced the significance of wāhine Māori in pre-colonial Māori society.

Read what witnesses said about:

Half-castes of Pomare's pa (Bay of Islands) by Richard Aldworth Oliver (1852) (pictured in document A121(b)). According to Oliver's accompanying text, the scene is at Kororareka (modern Russell) in 1851, during the feast (hākari) put on by Tamati Waka Nene. 'The man on the right with the musket is Neddy, who fought against us under Heki (Hone Heke) at Ruapekapeka. The girl next to him is Maria ... the woman with the baby is said to be the daughter of the Chevalier Dillon; and on the left is Jane, who was famous for her personal attractions ...The old lady kneeling on the right is "Na Nuia" Pomare's wife, who placed herself in that becoming attitude to avoid having her portrait taken.' 'Jane, who was famous for her personal attractions' may be Jane Gray, daughter of Alexander Gray and Kotero Hinerangi.’

Key witnesses who gave evidence

Dr Ngahuia Murphy (doc A67)(external link) presented in-depth evidence about practices associated with te whare tangata, including birth and menstruation. She emphasised the power and status held by wāhine due to their reproductive role, and detailed various ‘whare tangata rites’ which nurtured and balanced inter-generational connections, including birthing directly on the whenua, burying the whenua and iho in tribal lands, and returning menstruation blood – which Ms Murphy describes as the purificatory and renewing blood of the womb – to the earth. She also detailed various celebratory tikanga for girls entering puberty (some of which are now being reclaimed as a decolonial intervention), saying they showed whānau and hapū acknowledging the mana of wāhine.

Patricia Tauroa giving evidence virtually, pictured with Judge Sarah Reeves

Heeni Hoterene (doc A75)(external link) gave evidence about tīpuna whāea, wāhine, and the māramataka in Te Tai Tokerau. She emphasised that, due to their ability to give life, wāhine were vital to the sustainability and wellbeing of whānau, hapū, and iwi.

Heeni Hoterene giving evidence at Terenga Parāoa Marae, Whangārei, July 2021

Violet Walker (doc A66)(external link) reflected on the significant roles and responsibilities of wāhine Māori within the whānau before colonisation, as well as detailing various tikanga associated with pregnancy and childbirth.

Violet Walker giving evidence at Terenga Parāoa Marae, Whangārei, July 2021

Robyn York (doc A65)(external link) shared mātauranga about birthing that she had inherited from her grandparents – including healing practices and karakia.

Robyn York giving evidence at Terenga Parāoa Marae, Whangārei, July 2021

Raiha Ruwhiu (doc A93)(external link) gave evidence based on the kōrero passed down from her Ngai Tamahaua tīpuna about te whare tangata, including pre-birthing, birthing, and post birth practices; the burial of pito and whenua wahi; and menstruation. She explained that it was the responsibility of the whānau to care for a pregnant woman, with childbirth regarded as a sacred ritual involving both male and female assistants. The whānau also cared for the mother after birth, using techniques like mirimiri (massaging). The whenua (placenta) and pito (umbilical cord) was returned to the whenua (earth). The places where both whenua and pito were buried became wāhi tapu.

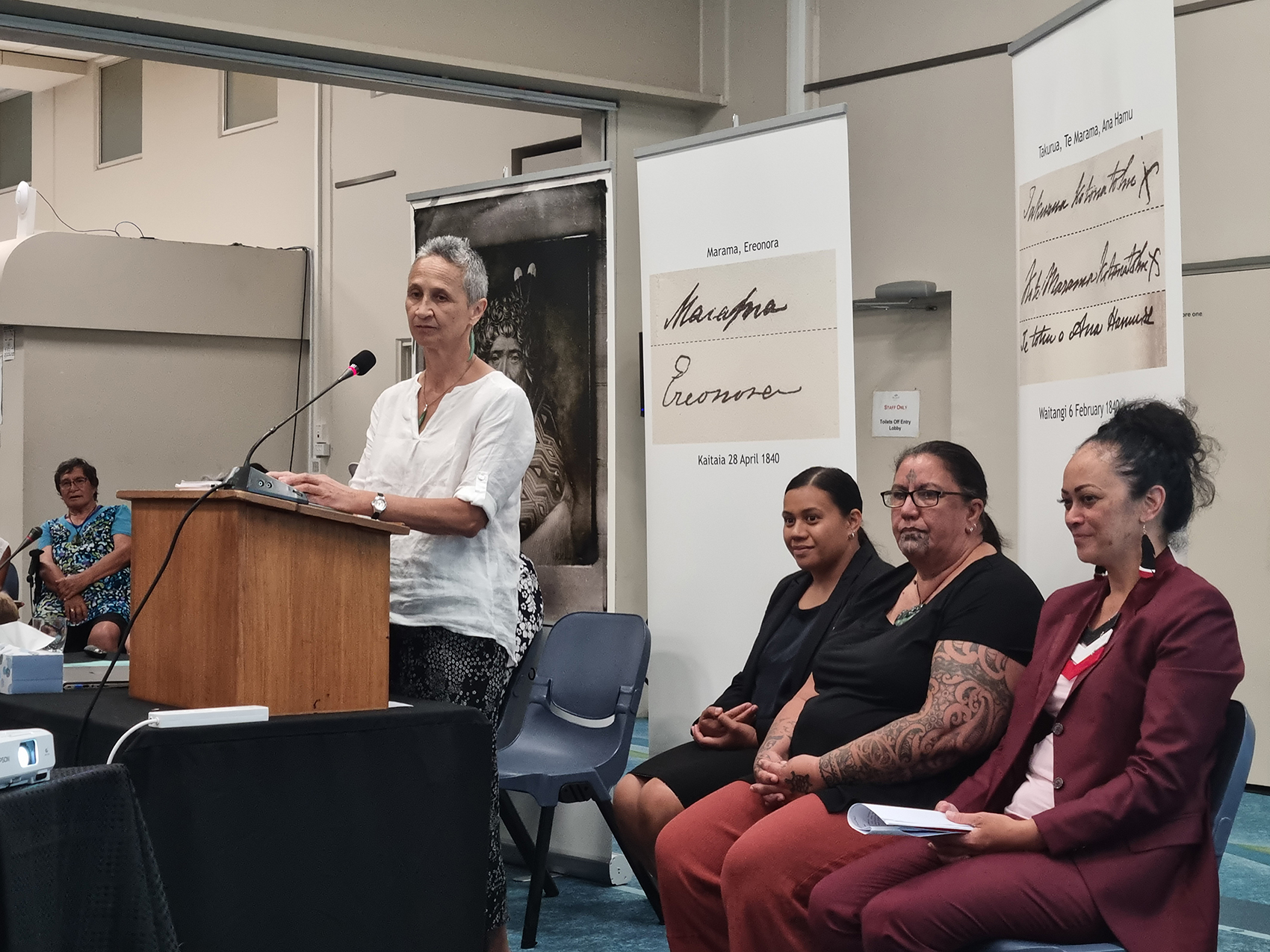

From right: Raiha Ruwhiu, Genevieve Ruwhiu-Pupuke, Kayreen Tapuke, and Tracy Hillier. Pictured at Te Mānuka Tūtahi Marae, Whakatāne, July 2022

Dr Hiria Hape (doc A114)(external link) gave detailed evidence, based on Tūhoe kōrero tuku iho, about practices associated with both childbirth and menstruation, detailing various restrictions on a menstruating woman due to the tapu of this time – including not attending pōwhiri, visiting urupā, or working the food garden.

Dr Hiria Hape giving evidence at Waiwhetū Marae, Lower Hutt, August 2022

Hera Black-Te Rangi and Mareta Taute (doc A116)(external link) shared the cautionary advice shared by her kuia relating to the tapu of women during childbirth and menstruation.

Mareta Taute and Hera Black giving evidence at Waiwhetū Marae, Lower Hutt, August 2022