Wāhine Māori rangatira

Ko ngā rangatira wāhine Māori

In all iwi and hapū traditions across the motu that were represented in tūāpapa evidence, there are stories and examples of significant wāhine who exercised mana in traditional Māori society – some of which are detailed below. This list is not exhaustive, neither of the stories in the evidence we heard, or of the multitude of significant wāhine in whakapapa across the motu. However, it provides a glimpse of the legacy of mana wāhine contained within the whakapapa of witnesses who presented.

Mana Wāhine inquiry panel pictured with Te Puea Herangi memorial

Stories of tīpuna wāhine: What witnesses said

Hine-ā-maru

Hine-ā-maru is the tipuna from whom Ngāti Hine derives its name. Drawing on Ngāti Hine waiata, pepeha, whakatuauki and pūrākau, Moe Milne (doc A62)(external link) explained that Hine-ā-maru was a spiritually powerful rangatira. She led her people on a heke from Waimamaku pā to Waiōmio after her father Torongare was exiled from their pā when he fell out with his wife Hauhaua. Many significant historical places and place names are tied to this heke. Ms Milne said that wāhine of Ngāti Hine have inherited traits of Hine-ā-Maru – they are ‘sharp, direct and decisive’, ‘strong in their ideas’ and strategic, forward thinkers. Hine-ā-māru remains a central figure in Ngāti Hine self-understandings and community life, to the extent that Moe Milne said ‘[i]t is common that marae within Ngāti Hine reserve an empty seat during formal proceedings for Hine-ā-Maru as a way of continuing to express their honour and respect for her. I have a seat within my whare that I have adorned especially for Hine-ā-Maru. I invite her into my whare so she can act as a kaitiaki for our whānau’.

Moe Milne pictured with Hirini Henare (left) and a mokopuna

Carving of Hine-ā-maru at Terenga Parāoa Marae, Whangārei

Maikuku

Maikuku is an important ancestress in Te Tai Tokerau from whom all hapū in the Bay of Islands descend. Heeni Hoterene (doc A75)(external link) said that Maikuku was an uri of Rahiri, a rangatira of Ngāpuhi, and the daughter of Uenuku-kuare and Kareariki. Maikuku was a puhi, and ‘was said to have a high degree of mana and because of this, her people installed her in a cave near Waitangi’. Ms Hoterene said that ‘Maikuku married Hua and had a child, named Te Rā, who became a prominent ancestor of the Ngāpuhi, Ngāti Rāhiri. The children of Maikuku and Hua provide genealogical links to all the major hapū from Hokianga to the Bay of Islands, to Whangarei, and to Whangaroa. They include Ngai Tawake, Ngati Tautahi and Ngai Takotoke, prominent claimants to Ngawha together with Te Uriohua.’ She said that the beach at the Waitangi Treaty Grounds was traditionally named Te Ana o Maikuku.

Heeni Hoterene at Terenga Parāoa Marae, Whangārei

Kuramārotini

Kuramārotini was the first person to set eyes upon and name Aotearoa according to Katarina Jean Te Huia (doc A115).(external link) Ms Te Huia said Kuramārotini was the daughter of Toto, a chief of Hawaiki. Toto gave Kuramārotini a waka called Matahourua, in which she eventually sailed with her companion Kupe.

Māhinaarangi

Māhinaarangi is a significant tipuna to many iwi, including Ngāti Raukawa. Naomi Simmonds (doc A134)(external link) helped lead a research project involving a 23-day, 380 km hīkoi by seven Ngāti Raukawa wāhine that retraced Māhinaarangi’s journey in order to ‘understand her story, her mana, and also … the changes that have occurred between her journey and ours’. Māhinaarangi was a descendant of Porourangi, Rongomaiwahine, and Ngāti Kahungunu, and the mother of two daughters, Rangitairi and Hinewaituhi, and a son, Raukawa. According to Ms Simmonds, ‘[h]er journey and her story of pregnancy and birth is a powerful example of the interconnection between whakapapa, whenua and wāhine’. Māhinaarangi possessed ‘agency and self-determination’ and political nous, she said, as shown when she united Waikato and Kahungunu through marrying Tūrongo.

Naomi Simmonds giving evidence about Māhinaarangi

Naomi Simmonds (left) with rōpū who retraced Māhinaarangi's journey

Muriwai and Wairaka

Muriwai and Wairaka travelled to Aotearoa on the Mataatua waka, whose captain was Toroa. Muriwai was Toroa’s sister and Wairaka was his daughter. When the waka came adrift, either Muriwai or Wairaka – iwi traditions differ – righted the waka, stating ‘kia whakatāne ake au I ahau’ (I will act like a man). Both wāhine are significant rangatira in the whakapapa of many witnesses who gave evidence in this inquiry, including those who affiliate to Ngāti Ira, Te Whakatōhea, Ngai Tamahaua, Ngāti Awa, Te Whānau a Apanui. Tina Ngata(external link) emphasised that Ngāti Porou’s relationships with Te Whānau a Apanui and Whakatōhea are founded on their shared female ancestry and the mana of Muriwai from the Mātaatua waka. Tracy Hillier said

"Muriwai is the tipuna that binds us as Whakatōhea as it is the whakapapa of Muriwai that brings all the lines of Whakatōhea together. Her union joined the two waka, Mataatua and Nukutere. Ngai Tamahaua recognise and uphold our connection to our tipuna Muriwai whom we describe as ‘he wāhine tapū, he ariki, he tapairu o Ngai Tamahaua’." (Tracy Hillier, doc A92, p 8).(external link)

Materoa Dodd said the mana of Muriwai and Wairaka was shown by them both having

"the mana to name places; to decree rāhui; to ratify boundaries; to place, lift and transgress tapu (i.e. to secure the waka); to have a sacred dwelling: te ana o Muriwai, because she held the power of second sight that was tapu; to have a land area and Marae (Wairaka) imbued with your mana and named after you, to have a house of learning (Tūpāpakurau) located within Wairaka, to have planted the first kumara in Aotearoa in the garden named Mātirerau within Wairaka." (Materoa Dodd, doc A98, pp 8-9)(external link)

Witnesses pointed to places and landmarks named for Muriwai as part of her continuing significance and mana today. These include whare tīpuna at Ōpape, Te Wai Mimiha a Muriwai (Muriwai Beach), Hiruharama Marae (the poutokomanawa is Muriwai), Tuapiro Marae (the dining hall is named Muriwai and the ancestral house is called Ngā Kuri a Wharei) (Genevieve Ruwhiu-Pupuke, doc A102;(external link) Raiha Ruwhiu, doc A93;(external link) Robyn Hata-Gage, doc A33).(external link) Owairaka is one place named for Wairaka.

The name ‘Whakatāne’ originates from the words uttered by either Muriwai or Wairaka, ‘kia whakatāne ake au i ahau’ (Whirimako Black, doc A84;(external link) Robyn Hata-Gage, doc A33(external link); Sharon Cambell and Dr Mania Campbell-Seymour, doc A39,(external link) doc A39(a);(external link) Te Kahautu Maxwell, doc A46).(external link) Anna Kurei said that Muriwai’s ‘action also set a precedent enabling subsequent generations of her female descendants to undertake male tasks with courage and fortitude when necessary’ (Anna Kurei, doc A100, p 5)(external link). Likewise, Materoa Dodd reflected on the continuing influence of Muriwai and Wairaka when she said that

"Wairaka and Muriwai are part of our hā (breath), they are our feminine dimension of the divine, their deeds are reflected in us, they shape who we are, their wisdom and ‘second sight’ guide a better future for generations to come." (Materoa Dodd, doc A98, p 17)(external link)

In the words of another witness, Waitangi Black, Muriwai and Wairaka are ‘the pinnacle of our [Ngāti Awa] Mana Wahine discussions’ (Waitangi Black, doc A101, p 6).(external link)

For more on Muriwai and Wairaka, see:

- Ngāti Ira narratives

- Te Whakatōhea narratives

- Ngai Tamahaua narratives

- Ngāti Awa

- Te Whānau a Apanui

Mural of Muriwai wearing a mataora, painted by Graeme Hōtere (right)

Amo on Wairaka Wharenui, with Urukakengarangi Lawson and Albert Percy (photographer) circa 1920s (pictured in document A98(b))

Muriwai tipuna whare (pictured in document A39(b))

Sharon Campbell and Dr Mania Campbell-Seymour, outside Te Ana o Muriwai ki Whakatāne

Waitohi

Waitohi was a ‘wāhine military strategist’ involved in conflicts between Ngāti Toa and Waikato iwi in the early 1800s. According to Elaine Bevan, Heeni Wilson, and Nganeko Wilson (doc A119),(external link) she was sister of Te Rauparaha, and the daughter of Ngāti Toa rangatira Werawera. Her marriage to Te Rākaherea, who was of a higher status, reflected ‘her character, her mana and her whakapapa’. She was the mother of Te Rangitopeora and Te Rangihaeata. She prevented an attack on Ngāti Toa from Ngāti Maniapoto at Ōhāua-te-rangi pā. She led militarily with her brother Te Rauparaha, calling Ngāti Raukawa to come down to the lower North Island to secure Te Rauparaha’s conquests. She also secured peace between Te Rauparaha and Te Rangihaeata while she was alive – and witnesses said that ‘when she passed, civil war descended straight after her tangi, including increasing division between Rangihaetea and Te Rauparaha’ (A119, p 3). She divided the land Ngāti Toa acquired through conquest between Ngāti Raukawa and Taranaki, and settled disputes over conquered land. Along with her daughter Te Rangitopeora, witnesses said that Waitohi played a role in apportioning land that Te Rauparaha won in battle, including identifying the boundary areas for Ngati Raukawa and Te Atiawa.

Heeni Wilson and whānau group at Waiwhetū Marae, Lower Hutt. Images of Te Rangitopeora at front.

Te Rangitopeora

Te Rangitopeora was a Ngāti Toa and Ngāti Raukawa rangatira who was the daughter of Waitohi and Te Rākaherea, sister of Rangihaeata, niece of Te Rauparaha, and mother of Mātene Te Whiwhi. She signed te Tiriti on behalf of Ngāti Toa and Ngāti Raukawa. Elaine Bevan, Heeni Wilson, and Nganeko Wilson (doc A119)(external link) said that Te Rangitopeora spoke on the marae, as ‘in her time there was not a golden rule for who could speak, it depended on the person’s mana, the rank of the wāhine’. She also had at least four marriages – which, witnesses said, demonstrated the agency of wāhine rangatira in traditional Māori society. Tania Rangiheuea (doc A22)(external link) shared Te Rangitopeora’s story through a creative first-hand narrative. Ms Ringaheuea described her as ‘a leader of her people during the early colonial period leading up to the signing of the Treaty and until her death sometime between 1865 and 1873’ who ‘exemplified every possible interpretation of the term “mana wāhine”’.

Turikātuku

Turikātuku was the senior-wife and principal strategist of Hongi Hika. Professor Angela Wanhalla said that Turikātuku ‘held mana in her own right and had a strategic and leadership role on his taua in the 1820s’ (Professor Angela Wanhalla, doc A82, p 4).(external link) Jessica Williams (doc A61),(external link) Keti Marsh-Solomon (doc A29),(external link) and Ripeka Evans (doc A21)(external link) also reinforced this kōrero about Turikātuku.

Hariata Rongo

Hariata Rongo was the wife of Hone Heke and, later, of Arama Karaka Pi. Keti Marsh-Solomon (doc A29)(external link) described Hariata Rongo as a woman of ‘great mana’ with ‘formidable whakapapa and intellect’.

Te Pūea Herangi

Te Pūea Herangi lived from 1883 to 1952 and was the grand-daughter of King Tawhiao. She influenced the Kīngitanga movement and the establishment of Tūrangawaewae Marae. Mamae Takerei (doc A32),(external link) a descendant of Te Puea Herangi and resident at Tūrangawaewae Marae, analysed a number of compositions by Te Pūea Herangi, which showed she was a leader with a ‘visionary sense’ who gave ‘hope to her people’. Sharryn Te Atawhai Barton (doc A49)(external link) is also a descendant of Te Puea Herangi and said ‘Princess Te Puea is the epitome of customary mana wāhine’ and ‘operated as a rangatira and gender never came into it. She was respected by other rangatira, and formed alliances rangatira to rangatira’ (doc A49, p 5).

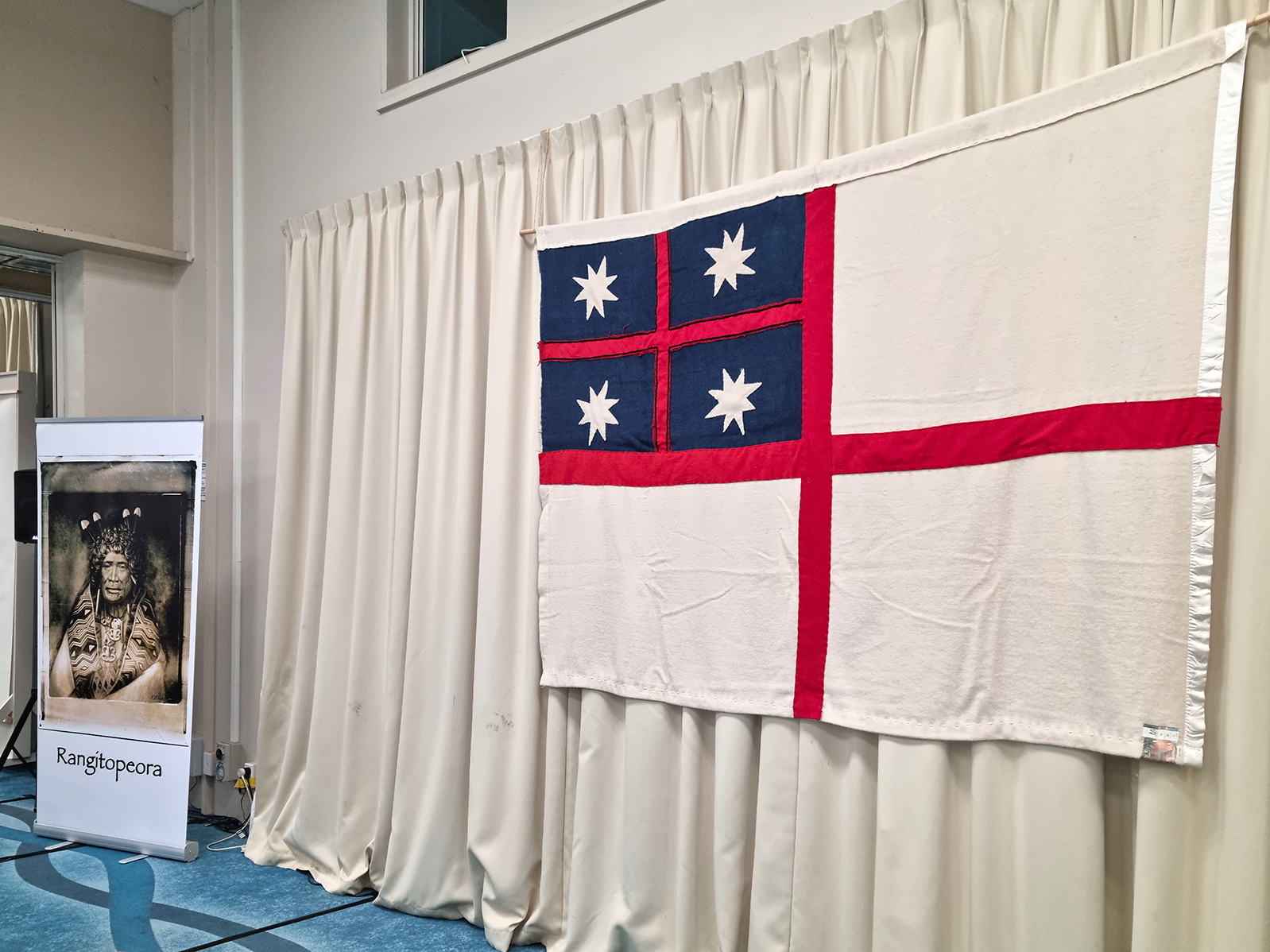

Mana Wāhine inquiry panel pictured with Te Puea Herangi memorial at Tūrangawaewae Marae, Ngāruawāhia

Wharekiri

Wharekiri was a Ngāti Rangatahi wahine born in 1828 in Kawhia, according to her descendant Mereti Taipana (doc A130)(external link). Although Wharekiri lived in a ‘tumultuous time of upheaval and extreme’, Ms Taipana said that her life story demonstrated that the mana of wāhine was not obviously different from that of tāne. Wharekiri was part of various Ngāti Rangatahi heke, including te Herenga Iai i raro, Ngāti Raukawa’s heke from Ohura to Otaki. She lived in Porirua, on Kāpiti Island and at Heretaunga in the Hutt Valley. In 1836, she had a daughter, Mihi Ki Turangi, to English whaler James Cootes (Hemi Kuti) who lived alongside Ngāti Toa on Kapiti Island. In 1846, when Ngāti Rangatahi was ‘forcibly evicted from the Hutt Valley [by the Crown]’, Wharekiri was part of a heke to the Rangitikei area where they eventually set up a new kainga (Miria te Kakara), south of the Rangataua stream. This traumatic heke showed her ‘strength, determination and rangatiratanga’. Ms Taipana also gave evidence about the life of Wharekiri’s daughter Mihi Ki Turangi (doc A130).

Mereti Taipana giving evidence virtually

Ruataupare

Ruataupare is a significant tipuna wahine for Ngāti Porou. Although she was not the eldest child in her whānau, Ruataupare ‘came to be revered as one of the bearers of the greatest mana within Ngāti Porou’, according to Tina Ngata (doc A88)(external link). Ms Ngata said that, although the military campaigns of her husband Tuwhakairiora came to shape the political landscape and land holdings of Ngāti Porou, ‘the mana whenua of this powerful union has always been recognised as belonging to Ruataupare’. Donna Awatere Huata (doc A20)(external link) also described Ruataupare’s relationship with Tuwhakairiora, who she said was ‘of a lesser whakapapa’ to his wife. As his military feats accrued, ‘people proclaimed a Hapū after him – Te Whanau o Tuwhakairiora’. Ms Awatere-Huata said ‘Ruataupare was angry that her Hapū, Te Whanau o Ruataupare was being eclipsed so left him (in Te Araroa) and founded a marae at Tuparoa, Te Rangi Weherua (signifying the day they parted) and her meeting house, Tangihaere (because she wept without ceasing) … She left for Tokomaru Bay where she brought several other Hapu into Te Whanau o Ruataupare’.

Hinetapora

Hinetapora was an Ariki descended from Tuwhakairiora’s second marriage to Ruataupare’s sister, according to Donna Awatere Huata (doc A20)(external link). Like Ruataupare, ‘she also married a man with a lesser whakapapa, Te Rangikapotua, the descendant of another great chief, the founder of the Uepohatu tribe, Uepohatu. Hinetapora was much revered by her people. When Tamahae was coming to wipe out her whanau, Hinetapora sent her people into hiding and waited for him. He cut off her head saying: “Ka nui tenei. He kotahi ia, he mano kei raro”. She is enough. Although there is one of her, she represents thousands’ (doc A20, p 10).

Donna Awatere-Huata giving evidence at Turner Centre, Kerikeri

Maraea Te Kuri o te Wao Paehangi / Maraea Cassidy (Katete)

Maraea Te Kuri o te Wao Paehangi / Maraea Cassidy (Katete) was born in 1814 and was the daughter of Moka Paehangi and Kohinewai. According to Ipu Tito-Absolum (doc A70),(external link) both Maraea Te Kuri o te Wao Paehangi’s parents were of ‘chiefly rank’ within Ngāpuhi. Her father, Moka Paehangi, was a signatory of He Whakaputanga / the Declaration of Independence, Hobson’s Proclamations, and te Tiriti o Waitangi. Maraea was one of his two daughters and ‘became one of the highest ranking waahine of Hokianga and accompanied her father to Australia on musket buying trips’. According to Ms Absolum, after catching sight of fifteen-year-old Irish convict Thomas Cassidy, ‘Maraea asked her father to buy him for her’. Cassidy was brought to Hokianga and they married when she was nineteen. In order to do so, she ‘was said to have become the first Māori woman to be baptised Catholic’. The couple had four daughters and three sons. Ms Absolum stated that ‘In those days, late 1700s early 1800s, alliances with Pakeha were highly valued for trading benefits and chiefs sometimes encouraged their daughters into relationships of that nature … but in our case, Maraea chose that path herself’. Her hapū, Te Mahurehure expected Thomas Cassidy to be a trader for them, but he ‘put a spanner in the works as he betrayed that relationship by drunkenness and illicit relations with a widow in Rawene. The worst is that he molested his oldest daughter Mere … Maraea, it is said, laid-in-wait for him in her father’s fortified village where they had their colonial house and assassinated him. She and daughters buried him in their open fireplace and cooked their food over the fire’. Ms Absolum also described the lives of Maraea’s children, who were also significant tipuna in her whakapapa.

Maraea Cassidy (pictured in document A70(c))

Ruaputahanga

Ruaputahanga was a puhi and chieftain whose betrothal to Turongo and later marriage to Whatihua (his brother) united the aristocratic lineages of Aotea and Tainui, according to Ripeka Hudson (doc A128)(external link). Ruaputahanga had several marriages and a number of places around the Taranaki region are named for her. Ms Hudson said Ruaputahanga ‘serves as a testament and example how wahine hold their mana’ as she was a ‘gifted, brave, courageous, and respected leader, the stories about her contain many examples including the capability of wahine to determine and exercise agency for their life and remain uncompromising in upholding and protecting her worth’.

Ripeka Hudson giving evidence at Waiwhetū Marae, Lower Hutt

Whakaotirangi

Whakaotirangi is a significant tipuna for many iwi and hapū, including descendants of the Te Arawa and Tainui waka (see: Melaina Huaki, doc A89, pp 2-3(external link)). A rōpū of uri of Ngāti Raukawa presented to the Tribunal about Whakaotirangi. Heeni Collins (doc A108)(external link) said that in early oral accounts about the settlement of New Zealand by Māori record Whakaotirangi as travelling from Hawaiki to Aotearoa with her husband Hoturoa, his other wife Marama, her son Poutukeka and his two wives and three of her cousins. Prior to their departure, ‘she had the important role of obtaining the mauri for the Tainui waka’ which indicated that she was a tohunga. Whakaotirangi is also said to have undertaken the important task of carrying the kumara tubers ‘which would help feed her people in the new land’ within her kete – ‘te kete rukuruku a Whakaotirangi’. In Ms Collins’ narrative, Whakaotirangi’s twin sister, Whakaotinuku, carried kumara to Aotearoa on the Te Arawa waka. Whakaotirangi also nurtured the mauri of the kumara upon arrival to Aotearoa, establishing a garden at Pākarikari near Aotea harbour north of Lake Parangi and east of Pukeatua pā. This garden was called Hawaiki, and Ms Collins said taro plants can still be seen growing there today. Ms Collins gave examples of the power of Whakaotirangi’s karakia, which shifted the Tainui waka when it was stuck at Otahuhu. Many lines of Ngāti Raukawa descent come from Whakaotirangi, and her diplomacy was important for keeping peace between the Tainui and Te Arawa waka.

Rākeitākiha

Rākeitākiha is a tipuna of Taranaki who was highly regarded for her propagation of harakeke. This kōrero is recorded in the Taranaki Iwi Deed of Settlement (2015), which Aroaro Tamati (doc A131) said reflects both the ‘societal priorities’ of Taranaki (‘the production of harakeke, which is likened to the unity of the people’) as well as the centrality of mana wāhine (doc A131, p 3).

Rauhoto Tapairu

Rauhoto Tapairu was a tipuna wahine who was the ‘guidestone and kaitiaki who steered Rua Taranaki to where he stands today, on the Taranaki coast’, according to Aroaro Tamati (doc A131)(external link). Likewise, Dennis Ngawhare said that ‘[a]ccording to mātauranga-a-Taranaki, in the earliest ontological narratives of these islands when living mountains bestrode the whenua, Taranaki maunga travelled from the centre of Te Ikaroa a Māui to Te Tai Hauauru led by the rock Rauhoto. Conversely, the tātai whakapapa of human ancestors retained by the iwi recall that there was a human woman named Rauhoto, and her husband was Rua Taranaki. They lived in the earliest era of human inhabitation in Aotearoa and are the eponymous ancestors of the tribe Taranaki. All surviving narratives agree that it was Rauhoto Tapairu that led Taranaki, whether maunga or man, to the area’ (doc A117, p 3)(external link). According to Ms Tamati, that narrative about Rauhoto Tapairu reflects the ‘highly valued status and position she had’ as well as the ‘principal nature of the female role in pre-colonial times’ to facilitate manaaki, tiaki and haumarutanga (leadership, equilibrium, safety and wellbeing). Ms Tamati explained that ‘Te Toka a Rauhoto Tapairu rests at Pūniho Pā, 27 kilometres south of Ngāmotu, New Plymouth. She is a constant source of identity, of connection, of ihi, wehi, wana and mana – wahine’ (doc A131, pp 3-4).(external link)

Hinewhare

Hinewhare was the youngest daughter of Hongi Hika and lived between 1817 and 1890. She was a puhi and, according to Louisa Collier (doc A26(b))(external link), exemplified all the qualities and dignity of a woman of the highest ranks, and was held in the greatest respect. Hinewhare’s name was originally Ruiha but, when Hinewhare was thirteen years old, she was abducted and held on board the ship of Captain Brind. When questioned as to why the daughter of Hongi Hika was on board, Captain Brind said that she ‘was from the “girls’ house”, or brothel’ – of which ‘Hine whare’ is the literal translation. Ms Collier explained that, while this name was a major slur against the mana of Hongi Hika’s daughter, she never gave it up, as a symbol of the colonisation of her people (doc A26(b), p 7). Later on, Hinewhare became a successful gardener which brought great wealth to her hapū. She married to George Wells, an American ship captain, with whom she had 10 children.

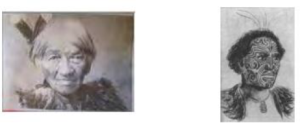

Hinewhare (left) and Hongi Hika (right) (pictured in document A26(c))

Kaiwhare

Kaiwhare was a puhi and ‘the originator of the Kaiwhare hapū, which is still recognised today’, according to Louisa Collier (doc A26(b)).(external link) Ms Collier said Kaiwhare was the first women in our [puhi] line to have the protection of Ngāpuhi. Her descendants include Hinewhare, Hariata Rongo, and Turikātuku.

Rangipāroro

Keita Hudson (doc A97)(external link) told the Tribunal the story of her tipuna Rangipāroro, from Onekawa Pā, above Ohiwa, and how she protected her new-born son Kahuki. Kahuki’s father was Rongopopoia who had been killed by the rangatira Tuāmutu. When Tuāmutu came to visit Rangipāroro soon after she had given birth, she knew he would want to kill Kahuki if he found out that he was a boy. However, her tapu status as a woman who had just given birth, meant that Tuāmutu could not go near her. She leveraged this to her advantage and, from the distance, was able to disguise Kahuki as a girl. She then fled with Kahuki to Te Kaharoa so that she could raise him safely away from Tuāmutu. Many places along her route were named after her journey and are recognised today, including the marae, Maromahue.

Rongorongo

Ripeka Hudson (doc A128)(external link) said that in Ngāruahinerangi narratives, the waka Aotea was carved and gifted to Rongorongo by her father, which indicated the mana and responsibilities she was ‘destined to carry’. Ms Hudson said that ‘Rongorongo’s navigational prowess and expert knowledge regarding waka, karakia, and Te Wao Nui o Tangaroa were entrusted to her from an early age’ and played ‘a pivotal role during the migration and settlement’ (doc A128, p 5).