Marriage and moe māori

Witnesses shared a range of perspectives on 'marriages' and unions between tāne and wāhine in te ao Māori before colonisation. Witnesses said marriage in te ao Māori was different to the European institution of marriage. First and foremost, it was motivated by whakapapa and bearing offspring. Wāhine had choice over who they married and had autonomy within the relationship itself, including the ability to leave a marriage. Witnesses also said it was common to have multiple husbands or wives or to remarry if needed. Witnesses also said marriages were frequently strategic and used as a way to increase mana, resources, whakapapa lines, and for peacekeeping.

Key witnesses who gave evidence

Professor Angela Wanhalla (doc A82) shared insights from her extensive research into intermarriage between Māori and Pākehā within a context of shore whaling. She emphasised how marriages between Māori women and Pākehā shore whalers were based on the authority of Māori women, not of Pākehā men. Indeed, these relationships uplifted the mana of Pākehā shore whalers within Māori communities, thereby allowing them to access resources and knowledge held by wāhine Māori. Her research reveals that ‘pre-1840 Māori women held rights over land and resources with the power and freedom to manage and direct the future of their land interests, including within marriage’. Professor Wanhalla highlighted that, despite the writing of some ethnographers and historians to the contrary, these marriages were strategic alliances based on tikanga Māori.

Professor Angela Wanhalla presenting evidence virtually, pictured with Judge Sarah Reeves

Moe Milne (doc A62) shared kōrero about marriage customs within Ngāti Hine. She said that tomo, or arranged marriages, were common practice in Ngāti Hine. In her words, tomo were ‘not marriage in the Pākehā sense, it was arranged ‘moea’, ka moea te tāne me te wahine, kia whai uri; the consummation of man and woman to produce offspring’. These marriages were used for the strategic purposes of strengthening whakapapa or brokering peace, and would be based on mutual understanding and responsibility for whānau and hapū wellbeing. She also said it was common for Ngāti Hine women to marry more than once, including if their husband passed away, if a couple were unable to have children, or in order to solidify alliances or strengthen connections to land.

Moe Milne giving a TV interview at Terenga Parāoa Marae, Whangārei

Dr Ella Henry (doc A63) described intimate relationships in te ao Māori before colonisation, including premarital sex, puhi, tomo, strategic alliances, and marriage ceremonies. She supported her discussion with contemporary academic work as well as that of early ethnographers – including Mākereti Papakura.

Dr Ella Henry pictured with her lawyers Natalie Coates (left) and Tara Hauraki (right)

Examples of tīpuna marriages

Witnesses also discussed many marriages and love stories of their tīpuna. This is a non-exhaustive list:

- Hinengakau married Tamahina of the neighbouring Ngati Tuwharetoa in a peace-making alliance. (Hinemoa Ranginui-Mansell, doc A129, p 7)(external link)

- Kohinetau, daughter of Te Rawheao, was a wāhine rangātira and wāhine toa. Following a battle between Ngāti Manu and Ngai Tu, she came across Te Kohuru, a famous Nga Puhi carver from Ngai Tu, and decided to marry him, thus sparing his life. (Marareia Hamilton, doc A121, pp 4-5)(external link)

- Te Rangingangana, daughter of Te Whatanui from Ngāti Raukawa and one of Ngāti Manu’s predominant wāhine Rangātira, married Ngāti Manu chief Pomare II in a strategic peace-keeping alliance. (Marareia Hamilton, doc A121, p 5)(external link)

- Maikuku was a puhi who married Huatakaroa thus forming kinships between Waitangi and Whangaroa. (Esme Sherwin, doc A110, pp 8-9)(external link)

- Āhuaiti was a mana wāhine who, through her union with Rāhiri, created our hapū, Ngāti Rāhiri. (Esme Sherwin, doc A110, p 9)(external link)

- Hēni Ngārino was a Waikato princess who formed a union with Maihi Kawiti in the North, thus cementing a strong bond Tainui Waikato and Ngāti Hine. (Esme Sherwin, doc A110, p 10)(external link)

- Waitohi married Te Rākaherea, brother to Pikoterangi, the King of Ngāti Toa. Her marriage to such a high-ranking family is an indication of her mana. (Elaine Bevan, Jane Wilson and Nganeko Wilson, doc A119, p 1)(external link)

- Ruaputahanga of Taranaki was a puhi and chieftain who refused many marriage offers until meeting Turongo, but subsequent events led her to instead marry Whatihua. Later, Ruaputahanga left Whatihua and re-married to Mokau. (Ripeka Hudson, doc A128, pp 8-9)(external link)

- Ruataupare was revered as the one of the bearers of the greatest mana within Ngāti Porou. She married Tuwhakairiora who led many significant military campaigns. Nevertheless, ‘the mana whenua of this powerful union has always been recognised as belonging to Ruataupare.’ (Tina Ngata, doc A88, p 6)(external link)

- Kura-a-whe-rangi, a descendent of Muriwai, married Tamahaua and led to the rise of the hapū Ngai Tamahaua. (Tracy Hillier, doc A84, p 8)(external link)

- Te Ao Putaputa pursued her love Tawhito-Kuru-Maranga and exemplifies the autonomy that wāhine held within marriage. (Tracy Hillier, doc A92, p 12)(external link)

- Turikatuku was married to Hongi Hika due to her skills as a tohunga. She was the military strategist behind Hongi Hika’s campaigns; ‘Hongi was the man holding the musket but the decision about the where, when, and how, was made by Turikatuku.’ (Bryce Peda Smith, doc A64, pp 2-3(external link); see also Violet Walker, doc A66, p 9(external link))

- Hēne Herengawaka had three tomo / marriages. ‘The first occasion was for Iwi relationship connections. The second tomo was within the Iwi to share the land care. The third tomo was … a form of restoring their relationship with Ngāpuhi because a whānau member of theirs had been harmed when visiting our whānau.’ (Te Miringa Huriwai, doc A53(a), p 6)(external link)

- Waitaha Māreikura married Hei, and together they had a son named Waitaha. This led to the rise of the Waitaha people. (Te Miringa Huriwai, doc A53(a), p 7)(external link)

- Hine-ā-maru was destined for a tomo but she did not go through with this and instead partnered with Koperu. This union solidified the alliance between Ngāti Hine and Ngāti Wai. The saying is ‘Ngāti Hine ki tai’ and ‘Ngāti Wai ki tuawhenua’ which is saying Ngāti Wai is Ngāti Hine on the coast and Ngāti Hine is Ngāti Wai inland. There is a kōrero that says that 70 pits of pipi were cooked in honour of Hine-ā-Maru as part of the celebration of their union. A feast of this size is a reflection of the great mana of Hine-ā-Maru. (Moe Milne, doc A62, p 22)(external link)

- Māhinaarangi’s union to Tūrongo is ‘heralded as one of the great love stories of Māori history [and] this union joined two chiefly lines’. Māhinaarangi ‘used her knowledge of the Raukawa tree and its leaves to create a perfume to create a lasting impression on Tūrongo. … When she was certain this union would be good for her and that her love would be requited, she revealed herself.’ (Naomi Simmonds, doc A134, p 6)(external link)

- Te Niho married Nihorere, the first-born daughter of Tuhuru, thus ending a war between Te Niho and Tuhuru. (Ema Weepu, doc A136, pp 12-13)(external link)

- The marriages of Hinetore to Huitao and Parekarewa to Haetapunui were arranged to reconnect the descendants of the two brothers Turongo and Whatihua, who had fallen out over a wahine and become estranged. There was also a re-connection between the Turongo and Whatihua descendants through the marriages of Raukawa’s sisters: Rangitairi married Uenuku-tuwhatu and Hinewaituhi married Motai II. (Heeni Collins, doc A108, p 2)(external link)

- Whakaotirangi, a wahine rangatira and tohunga, married Hoturoa, kaihautu of the Tainui waka. (Heeni Collins, doc A108)(external link)

- Matire Toha married Kati Takiwarua, making peace between Ngapuhi and Tainui. (Nora Rameka, doc A152(external link) and A152(a), pp 7-8)(external link)

- Te Ākau, a wahine Rangatira, married Hape Ki Tuarangi and thus helped to bind Te Arawa and Raukawa. (Stephanie Turner, doc A109, p 4)(external link)

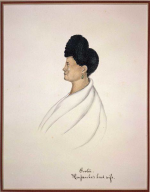

Pipi Kutia, daughter of Te Ākau and wife to Te Rauparaha, by Isaac Coates (pictured in document A109(a))

Drawing of Te Rauparaha (pictured in document A109(a))

What witnesses said

- “We know that couples existed and that they: ‘had certain exclusive rights and duties to each other, especially sexual ones’. Once a couple selected each other they might announce their intentions to cohabit or simply begin to sleep together in the whare of either the male’s or the female’s family. As long as no relative opposed the union they would come to be seen as a couple … Individuals in the tribe were not considered adult until they ‘married’ and had children … Those children who could trace their whakapapa through their mother and father were stable additions to the community. Prior to ‘marriage’, the sexual liaisons one engaged in should not result in pregnancy. If they did so, the relationship would need to be formalised by the community.” (Dr Ella Henry, doc A63, p 18)(external link)

- “[T]ono or betrothal was common, particularly among the chiefly lines, and a person who broke an engagement could create a situation where their family were the target of a taua (war party) sent to extract utu.” (Dr Ella Henry, doc A63, p 19)(external link)

- “Another aspect of Māori marital relationships, which reflects the status and role of Māori women is ‘marital separation’. [Jørgen Prytz] Johannsen notes that women were always free to dissolve their connection with a ‘husband’ and return to their people. No doubt, if this occurred her tribe would have cause for retribution in the form of utu, which would reflect badly on the husband, and could result in the exacting of costly revenge for the loss of mana to the wife and her whānau, because he had proven himself to be an inadequate marital partner.” (Dr Ella Henry, doc A63, p 20)(external link)

- “Māori did not marry in the Western sense and there was much more fluidity to moving in and out of ‘whakapapa’ relationships, depending on the contexts (which lands you were living on or moving to and what was happening). Whakapapa was the organising principle because of the relationships to the lands, not genders or patriarchal hierarchies. Rangatiratanga over land was held with both wāhine Māori and tāne Māori.” (Mere Skerrett, doc A137, p 8)(external link)

- “In Waikato, when your marriage was arranged, you would stay with your husband for the mana of the whenua and whānau. This was because tikanga emphasised the importance of these roles, which helped maintain balance in the greater hapū. Although the women would stay with the men, it remains on our marae, that we (wāhine) run the show. Wāhine and tāne knew their place. There was no whawhai between the wāhine and the tāne. It was tika that the wāhine sat down during the seasonal months and discussed the future of the hapū and iwi – not the tāne. Eventually, the tāne would join.” (Paihere Clarke, doc A141, p 3)(external link)

- “Te Tatau Pounamu or a greenstone door has been referred to throughout Ngāti Manu history. Used as a peace making the concept derives from the idea that greenstone represents the highest quality, and most chiefly of gifts. Multiple accounts of historic battles describe the gifting of wāhine Rangātira as instruments of enduring peace. Contrary to the belief that these events view women as possessions, it was of the highest prestige to be honoured in this manner. Furthermore, these types of marriages were strategic and had enduring political implications for the Hapū by way of continuing the whakapapa.” (Marareia Hamilton, doc A121, p 5)(external link)

- “Marriages outside hapu were usually for political purposes.” (Hinemoa Ranginui-Mansell, doc A129, p 6)(external link)

- “One of the powers of the mana wāhine was to implement strategic relationships. This would ensure generation, after generation had connection. Mana wāhine could help protect hapū from being wiped out. If wāhine were married off and strategically placed somewhere, they saved lives.” (Esme Sherwin, doc A110, p 8)(external link)

- “There was no stigma around having many husbands prior to colonisation. Women were not bound to a man, and as a mana wāhine, you could walk away and form a union, or form a new union if your man died. The only time you could not be with another man was if you were pregnant and mana wāhine would support these actions. If your man died and you were pregnant, you could not touch another man until you had given birth because you had to keep the seed clean.” (Esme Sherwin, doc A110, p 10)(external link)

- “My understanding of marriage in pre-colonial Māori society was that if people wanted to be together then they would choose to be with each other and if they wanted to separate, they would agree to separate. Upon separation, the community would wananga and decide whether it was what was best for the couple and the community for them to separate.” (Kayreen Tapuke, doc A94, p 10)(external link)

- “Marriages were fluid, there was no restriction on how many partners one person could have.” (Kayreen Tapuke, doc A94, p 10)(external link)

- “Tipuna tāne didn’t just marry anyone. There was a strategic purpose of the bloodlines for expansion of whenua tipuna [and] kaitiakitanga.” (Whirimako Black, doc A84, p 6)(external link)

- “In precolonial / pre-1840 Māori society, marriage was not ‘legal’ unless copulation was known to have taken place.” (Patricia Tauroa, doc A60, p 20)(external link)

- “Prior to colonisation, chiefs’ daughters were important as ‘gifts of peace’ to prevent any further bloodshed among warring tribes.” (Tiaho Mary Pillot, doc A91, p 8)(external link)

- “Customary Māori marriage held important social significance, and were categorised in several ways, ‘taumau’ arranged marriage, ‘moe Māori’, co-habitating, ‘tomo’, betrothed and ‘pakuha’ traditional wedding. Whakapapa was a vital component of the customary rules around customary marriage and was directly associated with land ownership. Arranged marriages were often politically motivated, as a result of protecting whānau land interests and resources for future generations and was consequently subject to considerably more tribal surveillance.” (Katarina Jean Te Huia, doc A115, p 11)(external link)

- “When a Māori woman married a Pākeha, her land became the land of the Pākeha male. This type of transfer of land did not occur in a Māori marriage. Whenua owned by Māori women only transferred into male ownership through whakapapa to a descendant.” (Patricia Tauroa, doc A60, p 8)(external link)